In the first of a two-part series, we spotlight the challenges parents and caregivers face in navigating special education in Portland.

At first, Neil Haigh was not that alarmed. This was early January and the Southwest Portland dad had gotten a call from school that his daughter Mattea’s feeding tube had come out, so could he please come fix it?

Mattea (pictured above with her father), a 10-year-old with blue eyes and golden hair, is nonspeaking and needs a range of medical supports, such as her gastronomy tube or “g-tube” that attaches like an earring in the wall of her stomach to provide her nutrition.

Haigh replaced the g-tube, and suggested that the Markham Elementary School staff receive additional training. But a staffer tipped him off that it wasn’t necessarily an adult who was responsible for the g-tube situation and when he got Mattea home, he noticed bruising on her arms.

“It felt like a bit of a cover-up and that’s when I got more involved,” Haigh says.

After weeks and hiring a legal team, the family finally got a copy of the incident report.

“[A student, name redacted] pulled out another student’s ‘mickey button’ which is part of their feeding apparatus,” reads the report. “The button was under the student’s clothing. Removing this button in this way takes significant force and it is painful to have it ripped out of the stomach.”

Mattea’s parents were shocked. Haigh started organizing with other classroom parents and discovered that the incident was just the “tip of the iceberg.” Kids were getting hurt, other parents alleged. And the classroom was struggling with a two-year-long string of teachers and support staff who had quit or left without returning, often citing a lack of support and safety.

“What happened to Mattea was awful, but it was a result of years and years of malpractice,” Haigh says. “We have no beef with (the child who removed Mattea’s g-tube). That kiddo is just a kiddo who has a lot of needs and wasn’t being adequately supported.”

There are 6,916 different experiences of special education in Oregon’s largest school district because, at last count, there are 6,916 special education students in Portland Public Schools (PPS). Guided by Individual Education Programs or IEPs — a team-designed plan for each disabled student’s particular needs — special education can be as simple as providing extra time to finish a test or as challenging as providing a one-to-one adult who can constantly, consistently, and instantly set expectations, react to changing conditions and buffer explosive behavior.

By some metrics, PPS’ special education department is doing well. The vast majority of special education students are integrated into the general education environment at least 40% of the time, with 81.3% integrated 80% or more of their day. The graduation rate for special education students sits at 82.4%, which is higher than the state target.

“PPS can stand up and be proud that that’s true,” says PPS Student Support Services Chief Jey Buno, of these statistics. “Because that’s not the same case everywhere else.”

Nevertheless, many people PDX Parent talked to for this series described a crisis in the district: safety risks to children and staff, overwhelming caseloads and a lack of action at the top.

This month, we’ll explore some of the challenges PPS is facing and how they fit into the national landscape. In November, we’ll look at some of the solutions proposed and how they might affect the next school year.

As for the Haighs, Neil says they tried hard to fix the Markham classroom but found the challenges insurmountable as the dysfunction was happening at the administrative-level for staffing and classroom design. The IEP team agreed to move Mattea to West Sylvan Middle School a few months early.

“West Sylvan has been eye-opening in the other direction in how good it is,” Haigh says. “It’s amazing how well that classroom is run, how the lessons are adapted.”

The pandemic’s long shadow

In 2015, Mary Pearson, then-head of special education at PPS, presented to the school board a bold vision for integrated classrooms across the district, where general education and special education teachers taught side-by-side, adapting a universally designed curriculum across the range of student needs. She called it Reach 2020 to imply that the vision would be put into place by the year 2020.

We all know what really happened in 2020.

The COVID-19 pandemic disrupted learning for all students, but a recent report from the Center on Reinventing Public Education analyzed the available data to find that, on the whole, disabled students fared worse. Though there is not much good data, indications are that those students generally have lower test scores, higher rates of intensified mental health concerns and fewer supports in place than pre-pandemic.

The pandemic also seems to have ushered in a wave of staffing crises. A March report from the National Center for Education Statistics says nearly half of the nation’s schools are struggling to fill at least one teaching position.

“Of schools reporting at least one vacancy, special education was identified as the teaching position with the most vacancies, with 45% of schools reporting this vacancy, followed by general elementary teaching positions (31%) and substitute teachers (20%),” reads the report. “Resignation was reported as the leading cause of teacher vacancies (51%), followed by retirement (21%).”

“We tried to go back to ‘normal’ — just to how it was before — and didn’t address for anyone in the building what we just went through. What we were doing before wasn’t totally working. And now we’re trying to do that thing still, and it’s completely not enough,” says Paulette Selman, a former school psychologist who now works as a special education advocate and education consultant in Portland.

Eoin Bastable is a Portland parent and a former program administrator of a rapid response team — a group of behavior intervention specialists that would get called into particularly tricky situations at schools.

“It continues to be a very siloed system,” Bastable says of PPS. “They don’t collaborate in the ways that everybody would like them to.”

He now produces a podcast and is raising a rising fifth-grader with an IEP. His son has Angelman’s syndrome, a genetic disorder that results in a wide variety of intellectual and developmental disabilities.

“What we noticed — at least in our family — is that the pandemic really exposed a lot of truth, I would say, in how students with disabilities are treated,” Bastable says. “The pandemic really revealed to me what some of the priorities are for the school district and I don’t think Portland is alone in that.”

Revolutionary program to end

The pandemic did have some silver linings: The federal government released billions of dollars in special one-time funding through stimulus plans like Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief or ESSER. Portland Public Schools says it served 949 students with about $2 million it received for “recovery services.” But that program ended this summer.

One group of parent advocates wishes PPS would learn from what worked during the pandemic: those whose children were students of PPS’ Online Learning Academy (OLA). Created in 2021, the program was a fully virtual option that several families felt worked well for their students. Among the 225 students enrolled in the 2022-23 school year, 71.1% were from what the district considers “underserved groups,” including 24% with IEPs.

PPS announced in January that it would be shuttering OLA. The district’s position is that there is no longer funding for OLA and no longer a need for the district to provide virtual learning.

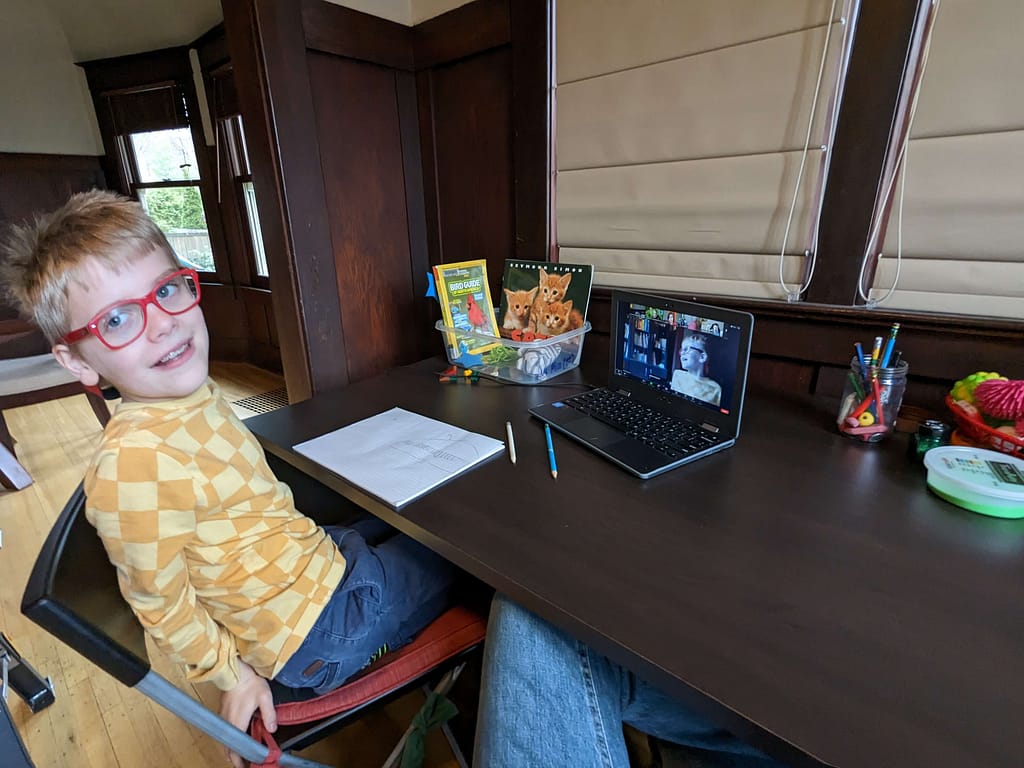

Hollis Blanchard says OLA was revolutionary for his autistic son, Reiter (pictured below), who was first enrolled in the program as a third-grader. Blanchard says Reiter previously attended Abernethy Elementary School, where everything from his behavior to his academics was “a huge struggle for him. And not just him. It was a struggle for us and for the staff and for the classmates.”

After moving to virtual school, Reiter has no discipline issues at all. He has been referred to Talented and Gifted services and excels in all his subjects.

“It’s night and day,” says Blanchard. “It is hard, but it is also so worth it.”

When Blanchard learned that OLA was shuttering, he organized parents, lobbied school board members, hosted a town hall meeting on the need for the online school and even fundraised for a lawsuit. But on May 24, he admitted defeat.

“To be honest, I’m not entirely sure what we’re going to do (for school next year),” he says, adding that Reiter might attend school outside of the district. “For many kids with disabilities, this (closure) is a really, really big deal.”

How is the administration responding?

Jey Buno wants to focus on the good. The district’s chief of Student Support Services and former special education director sees a lot of progress over the past year, both at the individual and district-wide level.

“I work with staff across the system that work really hard every single day to provide services and supports for students with disabilities,” Buno says. “The state of special education is we are all working collectively very hard to ensure robust services to students.”

At the beginning of the 2022-23 school year, there were about 70 open paraeducator positions (paraeducators, or paras for short, are staffers who provide support to teachers and students, primarily in special education). By the end of May, that figure had dropped to 11, of which five vacancies were at Pioneer Special School and three at DART schools, both of which are specialized programs for high-needs children. The district also started the 2022-23 year with 13 open special education teaching positions, but through recruitment and long-term substitutes, there were just two unfilled spots by the end of the year at Marysville K-5 and Harrison Park K-8.

“We’ve been to all the recruitment fairs in the Northwest,” Buno says, adding that human resources has several recruiters.

The administrator also pointed to $3,000 retention payments for paraeducators — a program started in the 2021-22 school year and ended in April 2023 that gave $1,500 bonuses in January and June for workers who stuck around.

Otherwise, compensation is part of the ongoing bargaining process with PPS’ unions — most notably Portland Association of Teachers and the Portland Federation of School Professionals. The district dismissed many of the complaints about their leadership as a bargaining tactic. [Editor’s Note: We’ll hear from the teachers’ union in the next installment.]

“When you say it’s a ‘crisis’, I’m kind of defensive of my staff — all the staff: the SLPs, the PTs, the OTs, the paraeducators — because they put their hearts and souls into it,” Buno says, referring to speech-language pathologists, physical therapists and occupational therapists. “Is there work to be done towards improving inclusive practices? Yes. Is there work to be done towards increasing our graduation rates? Yes. Is there work to be done on increasing our achievement rates? Yes.”

But Buno continued: “I don’t know that that’s different than any other school district in the metropolitan area, or in the Northwest United States, or even the entire country. And we want to own that and do that work. We want to be responsive to our parents. We want to be responsive to our kids, more importantly, and we want to center their experiences.”

“In the end,” Buno says, “I actually believe we’re all part of the same collective team working towards the same goals and supporting our kids, and our families and our communities.”

Next time:

The one thing teachers, parents and school administrators can all seem to agree on is the need for more school funding. We take a look at the legislature’s budget and other changes that may be coming for the 2023-24 school year.