Portland’s schools are contending with a chronic shortage of qualified teachers. What’s driving them away — and how can we win them back?

Anyone who has been paying attention to our schools — and likely even those who haven’t — knows that education in Oregon faces huge challenges. While we have many wonderful schools and exceptional educators, the past few decades have brought a compounding litany of troubling issues, including: decaying, neglected buildings; chronic underfunding; growing equity concerns; lead in the water; turmoil at Portland Public Schools (PPS); unacceptable achievement gaps; increasing class sizes; severe budget shortfalls; short yearly instructional hour requirements; year after year of bond measure requests; and the looming PERS funding crisis. An issue that we don’t hear much about, however — and which is a byproduct of all of the above —is the troubling trend of teacher and substitute teacher shortages.

There is good reason to think some of these problems are finally beginning to turn around. PPS is under new leadership, graduation rates are slowly improving, equity issues are starting to get their due, buildings are being rebuilt, and our budget crisis has been partially addressed by the new $2 billion school funding bill HB 3427. (Truly confronting the ballooning PERS costs continues to be put off.) However, our growing teacher shortage demands immediate attention.

Exact numbers are difficult to pin down because they aren’t comprehensively collected, but we know schools are struggling to fill teaching positions and maintain a ready supply of substitutes, which points to a shortage. Districts across the state report significant drops in the numbers of applicants for jobs, particularly for the hardest-hit areas, which include special education, math, science and specialty topics, says John Larson, president of the Oregon Education Association (OEA). Additionally, it’s even more difficult to attract culturally diverse or multilingual educators.

A Nationwide Problem

Portland metro’s teaching shortage reflects statewide and nationwide trends, with districts across the country taking drastic measures to recruit more teachers — from slashing licensing requirements to importing teachers from abroad. Educators across the country are taking to the streets in record numbers to protest substandard teaching environments, lack of support, lack of respect, lack of autonomy, lack of funding, and lack of pay, in demonstrations like the Oregon teachers’ walkout on May 8, which closed schools and called for increased education funding.

“I did a story in 1977 about the teacher shortage and how to recruit more minority teachers in PPS and Beaverton,” says Oregon State Sen. Lew Fredrick, a former reporter and PPS teacher, and a current member of the State Board of Education. “It’s over 40 years later and we’re still working on it.”

Anecdotal experiences, such as my fourth grader coming home last spring from his eastside PPS elementary school excited to tell me his principal was his teacher for the day, and his teacher’s comment that finding subs is a common problem for PPS, don’t immediately set off alarm bells. But when you start asking around, a disturbing pattern of stories emerges, from teachers who report coming in when they’re sick because a sub couldn’t be found to schools receiving just two applicants for a job that used to draw 100.

Teacher Burnout

“Teaching has become increasingly difficult nationally and specifically in Portland,” explains Suzanne Cohen, a teacher in PPS since 2002 and current president of the Portland Association of Teachers (PAT). “Teachers can get really bogged down and need a schedule that supports the workload.” What can we do to reverse these trends? “I wish the solutions didn’t always come down to more money but they always do. More supports mean more money,” says Cohen, expressing a viewpoint repeated by just about everyone else I interviewed.

All the metro districts I spoke with agreed that elementary full-time classroom positions were the easiest to fill, while finding bilingual, bicultural, STEM, racially diverse and special-education teachers was becoming more and more of a challenge. “It comes down to pay, support, respect,” echoes Sen. Fredrick, who is on a mission to recruit more teachers of color and believes that revenue from the new school funding package might finally start to turn the tide.

“I can tell you that we have some pretty big pockets of need around special education and bilingual education,” says Debbie Ebert, a former elementary school teacher and principal, and current Tigard-Tualatin School District (TTSD) human resources director. “It has been really, really difficult to fill those positions.”

There are huge issues in culture and discipline, limited resources, higher class sizes, and mounting paperwork. “We need to help teachers feel supported and manage caseload,” says Cohen, so that they can put more attention on the job of engaging kids in learning. Other concerns echoed by OEA, teachers, administrators and policy-makers include: plummeting respect for the teaching profession, fewer professional development opportunities, higher stress levels due to lowered resources coupled with greater workloads and more demanding classes, lessened autonomy in how curriculum is taught, too much testing, curricula that seem to change every few years, and growing safety concerns about dilapidated buildings, disruptive behavior, and the threat of school shootings.

This looming crisis may not get the press of the PERS predicament or the contaminated-water scandal, but statewide teacher and substitute teacher shortages are just as impactful.

“I was exhausted and no matter how much I worked to learn and improve, the job seemed to get harder and harder every year,” explains Sarah Pemberton Kastrup, who taught in PPS for 12 years as a classroom teacher in elementary and middle school before switching careers. “With 33 kids in my class that last year, it was impossible to meet all the kids’ needs, and I was really frustrated to be working so hard, to never actually be finished with the work, and to still know that kids were falling through the cracks.”

Which brings us to the trickiest thing about this topic. It’s not that there aren’t enough licensed teachers to fill the jobs, it’s that many of these educators are simply choosing to leave the profession. In fact, during the 2017-2018 school year, there were 26,659 licensed teachers in the state not teaching. “We’re seeing teachers quitting mid-year. The first, third and fifth years are big ones for teachers to leave the profession,” says Cohen. Unfortunately, burnout has become all too common. “A lot of teachers are really stressed out,” agrees veteran Grant High School social studies teacher Don Gavitte. Particularly new ones, he says, who don’t have the deep reservoir of experience, skill and colleague relationships that most veterans do.

Tough Shoes to Fill

Overworked teachers are also squeezed by a shortage of substitutes available to fill in for them when they can’t make it to class.

“Not having a substitute doesn’t just throw off your class; it has a ripple effect in the whole building,” explains Terri Harrington, longtime Oregon teacher and current substitute in the TTSD. Gavitte reports having been asked to fill in for other classes at Grant, at the last minute, five or six times last year — a big uptick from when he began teaching 19 years ago.

Where did the substitutes go? “If you are trying to make a living, being a substitute is a difficult way to do it. The work is incredibly unsteady and relatively low-paying and there is no incentive to take the hardest placements,” explains Harrington, who went back to subbing when her husband lost his job. Also, a strange dichotomy exists: While schools report trouble getting enough subs, subs report having trouble getting on lists, noting that if jobs aren’t grabbed “instantly” they will be taken. Lower pay, inconsistency and ineligibility for unions and health insurance (in some districts) also contribute to teachers’ reluctance to work as substitutes.

“There is a lot of pressure, it’s not easy and you get a lot of flak. It really is harder now,” says Linda Ingalls, a veteran PE teacher who has taught in Oregon at all levels for over 40 years, and has subbed for the past 12 in Wilsonville and Oregon City. Behavior issues are of particular concern. “It can get a little scary,” she says. “Sometimes you worry, ‘Oh my gosh, he could come back with a gun.’ I never thought about anything like that before.”

This issue stays relatively hidden because the bulk of it plays out behind the scenes, with administrators scrambling and teachers shifting to fill spots, and the problem is even more acute when it comes to specialty substitutes. Within PPS, the rate for filled regular classroom substitute jobs hovers around 96 percent, while coverage for paraeducator positions plummets to an average of 61 percent, with some schools dipping as low as 20 percent. “This is why many educators don’t stay home even when they should,” notes Harrington.

Still, some are staying home a lot: PPS teachers are absent an average of about 16 days per year, a rise of 13 percent over the past five years. This amounts to a lot of days to fill and points to teacher burnout and excess job stress. Unfilled substitute jobs rose just 3 percent in the past five years, but the total number of absent days quadrupled from around 400 to 1,600. This picture was even more dire in special education, where about 4,500 jobs were left unfilled.

Retain and Recruit

Another challenge compounds the shortage of both subs and full-time teachers, and it’s a geographic one: Just to the north of us in Vancouver, teachers are paid more and have smaller class sizes, which shrinks our pool of potential teachers. We also see the same disparity playing out in our state with the better-funded, better-performing schools attracting the most applicants. This leaves schools with larger historically underserved populations and higher levels of need adversely affected, such as in the TTSD, where students of color make up 42 percent of students and students learning English 30 percent.

So there is as much a pressing need to recruit new teachers as there is to retain the experienced teachers who burn out, look across the river for work, or decide to pursue more lucrative, less demanding jobs outside of education. “At the end of the day it all comes back to money, because in a booming economy educators have other options,” says Cohen, who also blames Portland’s high cost of living as a reason for teachers switching professions. According to a recent study by the Economic Policy Institute, the ratio of teachers’ wages compared to the wages of other college graduates is consistently lower: They earn just 77 percent of what their non-teaching peers earn.

The Group Joint Committee on Student Success, which spoke with hundreds of students and teachers across the state, also noted the ballooning impact of mental health issues, reports Sen. Fredrick. Student anxiety, homelessness, PTSD, language, economic and social issues, and special education are just a few of the considerations teachers now take on and need much more help to effectively tackle. “Social and emotional learning pieces are a brand new addition to the teaching profession, which makes it a lot harder,” echoes Hilda Rosselli, Ph.D., college and career readiness and educator advancement policy director at Oregon’s Chief Education Office.

“Now, there is a lot more inclusion, and I’m totally for that, but it makes teaching a lot more challenging,” notes Ingalls, who says this is why the extra teacher support and consistent, schoolwide disciplinary guidelines are so vitally needed, as well as strong, supportive administrative leadership to back up educators.

“As a state, we care deeply about having teachers that mirror the demographics of students,” says Rosselli, who reports that 38 percent of students in Oregon are ethnically diverse versus 10 percent of teachers. “We’re working on adding state funding to support a dedicated amount for mentoring and the support of educators at every stage of their careers.” Plus, she says there is added focus on “paying careful attention to how we recruit, hire and support educators of color and inspiring people to pursue the profession.”

‘Let us build it’

When it comes to the future of education in Oregon, Otto Schell, Oregon PTA’s legislative director, is hopeful: “After 30 years of cutting programs, laying off educators and disinvesting in our schools, this new funding would help to open doors of opportunity for all Oregon students — allowing us to recruit and retain a diverse group of teachers and school support staff.” Over the past few years, Oregon has implemented more recruitment and scholarship programs, such as the Portland Teachers Program and the Diverse Educator Pathway Program. In 2015, Oregon’s Department of Education launched its Teach in Oregon website (Teachin.Oregon.gov), which operates as a one-stop shop for prospective teachers, even offering information on available scholarships such as the $5,000 grants available for diverse teaching candidates.

Lisa Morawski, Gov. Brown’s interim press secretary, points to the governor’s newly created Educator Advancement Council, which “will deliver these supports, to diversify the educator workforce and foster teacher leadership in achieving student success in our classrooms and in every school community.”

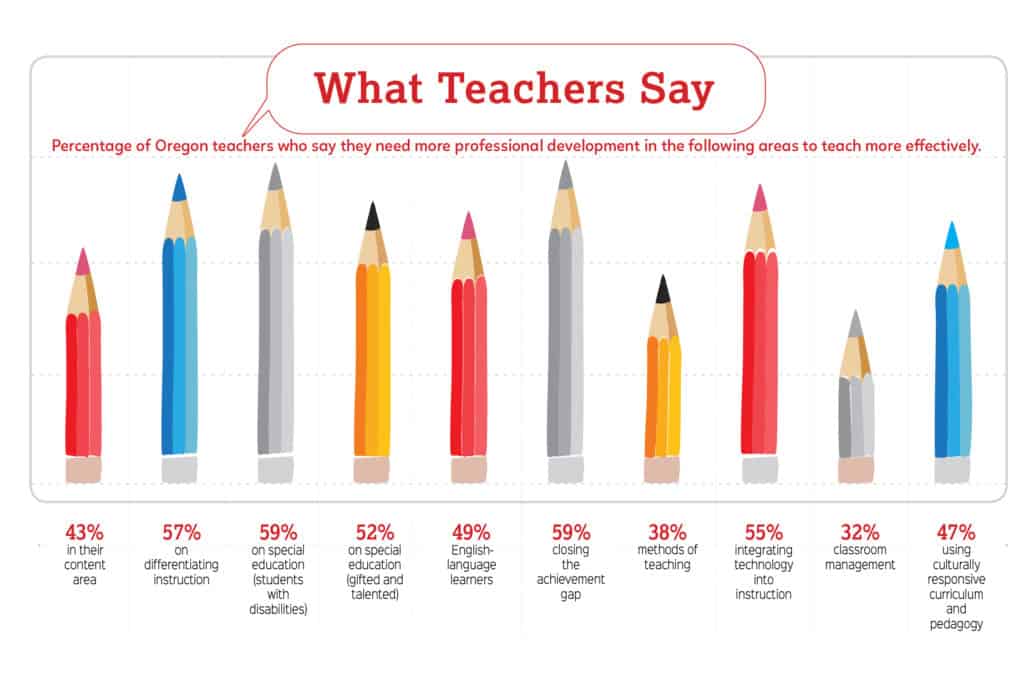

But much work still needs to be done. According to the 2018 Teaching, Empowering, Leading, and Learning (TELL) survey, which approximately 54 percent of Oregon’s 36,092 educators took part in, 60 percent of teachers feel the key to strengthening recruitment and support of educators is to include the voices of classroom teachers in decision-making regarding professional learning priorities, educator supports, and policies impacting teachers at the school, district, region and state levels. The majority of Oregon teachers also want more professional development. (See What Teachers Say, above.)

“The job can start to feel like a machine,” explains Gravitte. Instead, teachers want more agency. “Hand us the basic curriculum, but let us build it.” He also suggests moving back to a department-head model, where experienced teachers can take novices under their wing. “That’s where the money really needs to go to help young teachers thrive. The focus should go back to what really matters — that kids are engaged and learning.”

- 9 Ways to Save on Summer Camp - March 5, 2024

- Are Your Kids Ready to Stay Home Alone? - August 22, 2023

- The No Slacking Portland Summer: How to Keep Your Teen Busy - April 4, 2023