Public school funding is complicated. But we explain what you need to know about where the dollars come from and how they are spent.

If you know anything about schools and money, it’s that they don’t have enough, right?

But where does it all come from? And where does it all go?

Time to take some of the mystery out of school budgets.

It won’t be easy, especially in Oregon, where property tax laws passed 30 years ago created a funding landscape that gets more bizarre with each passing year.

In 2019, Oregon Democrats attempted to patch up these school funding gaps with the Student Success Act. That corporate-activities tax was expected to bring in $2 billion every two years. But now COVID-19 has put question marks around everything. As of this writing, state economists were expecting the additional money to add up to more like $1.2 billion each biennium, or two-year period.

We at PDX Parent don’t have a crystal ball, so we don’t know how much money will ultimately come through in these uncertain times. But we can tell you how Oregon’s school budgets are set up to work.

Where does the money come from?

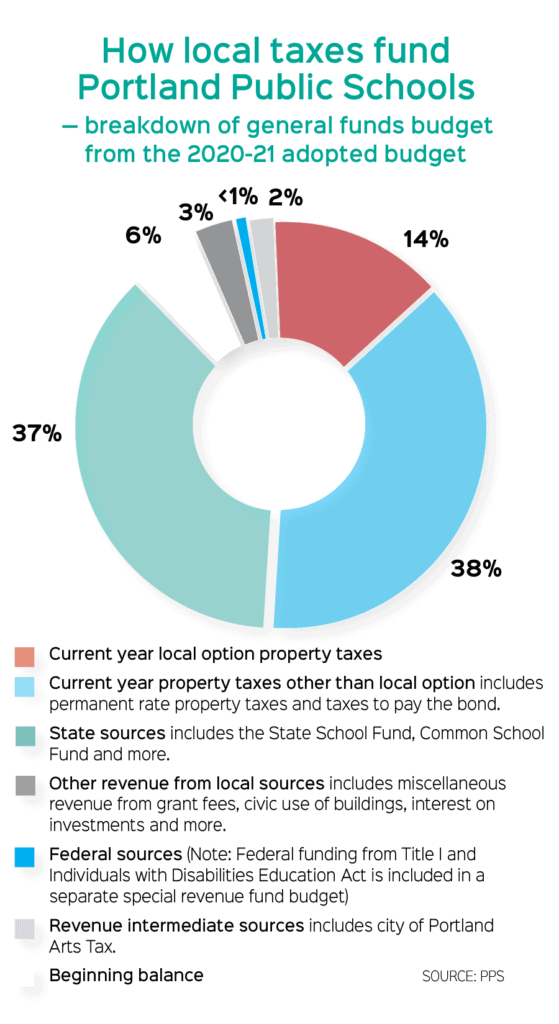

At its most basic level, an Oregon public school gets its funding through three primary sources: local property taxes, state income taxes and federal grants.

Property taxes used to be the main source of a school’s money, and districts do still get significant distributions from the counties they serve. Many districts have also asked voters for extra property taxes — to fund bond programs (typically for building or improving schools) or local option levies.

But three decades ago in Oregon, anti-tax initiatives shifted a major portion of the responsibility for school funding to the state. Those anti-tax measures gave schools a maximum dollar amount they could collect, and froze taxable property values — the combined effect was for schools to ask the state legislature for help. These days, K-12 education makes up about 40 percent of the state’s budget. The state’s general fund money comes almost entirely from income taxes.

Federal dollars come through various sources: the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act for special education, Title IV-B for after-school programs, Title II for teacher professional learning, etc. But a major source of funding is Title I, given to schools that serve communities where more than 35 percent of children are in poverty. In Oregon, more than 550 schools — about half — are eligible for Title I dollars.

April Olson directs federal programs for Reynolds School District, where 14 out of its 16 schools are now Title I.

For each school, the award amounts to an extra $200,000 to $300,000 per year. It’s spent according to a detailed plan — typically adding teachers or specialists, or even for wraparound services like food or counseling. Olson says the pandemic could affect Title I dollars in the future, but she’s more immediately worried about the effect of the 2020 Census. That’s where Title I gets its figures for how many children live in poverty in a school’s attendance area.

“I’m worried that with the current political climate — either through direct limitations on census collection or fear of people to participate — that [the count] will be under-represented,” she says.

Other sources

Beyond local, state and federal tax dollars, there are other sources of revenue for public schools. The controversial marijuana tax, which started accruing in 2016, is expected to raise $133.2 million this fiscal year. The State School Fund will get 40 percent of that, or about $53.3 million, to split among Oregon’s more than 1,200 schools.

The Common School Fund — not to be confused with the State School Fund — is a trust set up at Oregon’s founding. Managed timber sales and other natural-resource extraction fuel this account, which distributes about $50 million a year.

The Oregon Lottery allocates 53 percent of its money to education, which includes colleges and universities. Video lottery machines were shut off at the beginning of the pandemic, though, and the lottery is expected to bring in about half as much money this year. The Education Stability Fund, which is funded by lottery dollars, can be tapped in a recession, but lawmakers will have to decide how much to save for the future.

Parent Teacher Associations and booster clubs at individual schools can raise money, too, of course, but the money can’t go to pay for teachers. Those sources typically fund materials, trips, athletics, playground equipment, events or other “extras.”

School foundations can pay for extra staff. At Portland Public Schools, about a third of the neighborhood schools’ foundation money does go to a districtwide pool, but some argue that the extra funding that can be raised through a foundation at wealthier schools is inequitable. The Fund for Portland Public Schools reports that in 2018, its schools collectively raised more than $4.6 million.

Where does the money go?

After the anti-tax measures of the 1990s, lawmakers had to come up with a strategy for making sure schools got a “fair” slice of the pie.

As Oregon Department of Education’s Director of School Finance Mike Wiltfong says, “It’s not a simple: ‘Here’s how much money we have,’” and then the state spreads it around like peanut butter on toast. Instead, the state uses a complicated distribution formula that tracks how many kids are in each school and how many of those fall into a category of extra need. For example, students who qualify for special education get a double weight in the formula, students who aren’t native English-speakers earn 150 percent, etc.

Although districts are provided funding based on the student need formula (called ADMw or Average Daily Membership weighted), the dollars are not tied to any particular student. Oregon schools get distributions based on how many students are enrolled come October, which could be tricky if large numbers of students enroll at a charter school outside of their district or stop “attending” virtually. After 10 days of no-show, students are automatically unenrolled.

Approximately 85 percent of public education funding goes to staff salaries and benefits. That is why you may have heard what a big deal it is that Oregon doesn’t have enough money for the retirement benefits it promised to public employees. The Public Employees Retirement System (PERS) hasn’t brought in the anticipated revenues from its investments, which means schools may have to backfill from their own budgets.

That, says Wiltfong, is a “very serious consideration when we’re talking about budgets for school districts moving forward.”

After personnel costs come busing contracts, curriculum materials, professional development, central-office programs, nutrition programs, building maintenance and a rainy day fund.

Tigard-Tualatin School District Chief Financial Officer David Moore says his district’s 12 percent rainy day fund has allowed them to stabilize funding through Oregon’s rather volatile revenue system.

“I’m not shy about saying we budget pretty conservatively,” Moore says.

Maureen Wolf, president-elect of the Oregon School Boards Association and a Tigard-Tualatin School District board member, says elected school officials don’t tend to involve themselves in day-to-day expenses. Instead, they can direct money into long-term investments and planning, such as technology goals or new schools. Sometimes they will set directives on things like class size limits, which translates to a mandate to hire more teachers.

After all that, school principals are left with a bit of pocket money.

“It’s not a very large amount of money,” says Kristyn Westphal, area senior director for middle schools at Portland Public Schools and formerly the principal of Hosford Middle School. “On the order of a few thousand dollars.”

They use that to buy copier paper, mail grade reports and maybe offer a few extra staff hours for an after-school event.

“… in a normal year. When we’re not in a distance situation,” Westphal says. “How principals chose to spend their money this year will look different because we’re not needing as many physical resources.”

Westphal says each school will have a site council or other ways for parents to get involved if they wish. At Title I schools, there is actually a federal requirement for parents to be involved in deciding how that money is spent, so talk to your school’s principal.

“They can resolve a lot of questions that folks might have,” Westphal says.

All in all, the process for any given school year — from predicting funding, to setting a budget, to receiving the final allocation — takes 30 months. That means the process for the 2020-21 school year started long before the novel coronavirus shut down schools. And no one is sure what impact COVID-19 will have on tax revenues for the future.

“It’s a bit ominous where we’re headed into the next biennium,” Wolf says. The Oregon legislature will sort out the 2021-23 budget next spring.

Expenditures per pupil

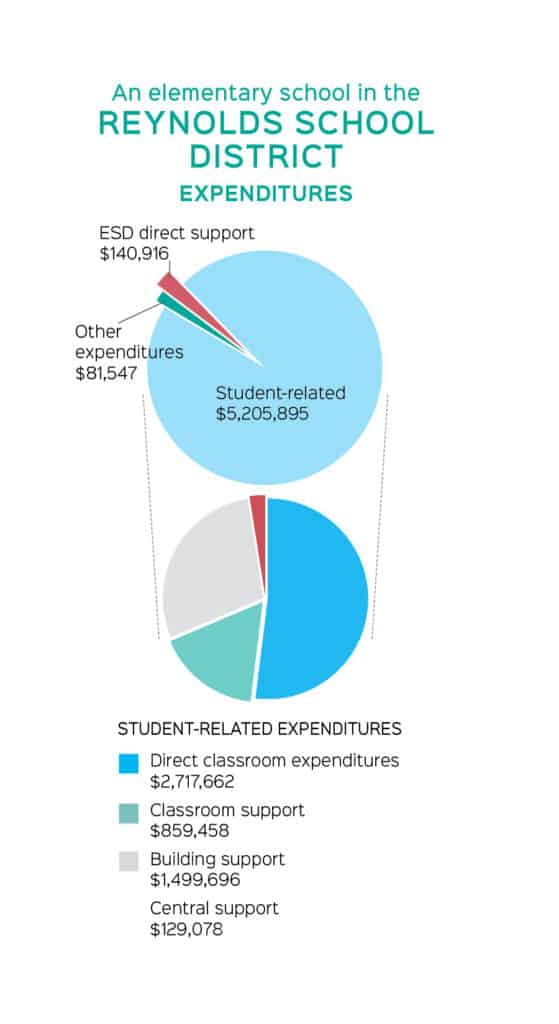

An elementary school in the Reynolds district with 20%-30% ESL students, fewer than 20% of students requiring special education services, and with a 20%-30% poverty rate, spends $15,798 per student.

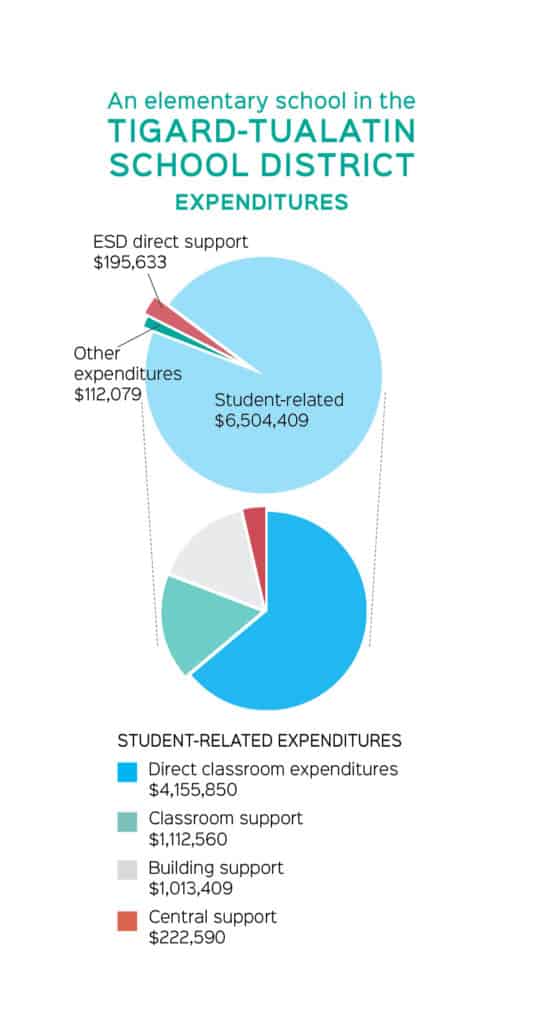

An elementary school in the Tigard-Tualatin district with less than 10% ESL students, fewer than 20% of students requiring special education services, and with a poverty rate of less than 10%, spends $12,392 per student.

An elementary school in Portland Public with less than 10% ESL students, fewer than 20% of students requiring special education services, and with a poverty rate of 10%-20%, spends $14,716 per student.

Anything else K-12 dollars go to?

There are 19 education service districts (ESD) in Oregon. These special districts tend to cover the rare and costly needs of a cluster of school districts, such as technology and curriculum purchases, and schools for at-risk students and those with significant medical challenges. They also tend to be the ones offering programs for qualifying students from birth to age 5, and ages 18 to 21. Education service district funding generally comes from contracts with component districts and the State School Fund.

How do charter schools work?

By law, all charter schools in Oregon are publicly funded. Each school works out its own agreement with its chartering district, but usually they get about 80 percent of the ADMw (Average Daily Membership weighted) funding for their students, and the other 20 percent goes to various administrative costs at the district level.

What about private schools?

Private school financing is much simpler than public schools, says Mark Siegel, executive director of the Oregon Federation of Independent Schools. OFIS claims a quarter of Oregon schools are privately operated and serve 11 percent of Oregon’s children.

Private schools are all different. They range from tiny operations attached to churches, to K-12 or upper schools with endowments and everything in between.

Tuition covers the bulk of the expenses at these schools, Siegel says. Donations typically go toward facilities. Some schools are lucky or large enough to have endowments, and those tend to go toward facilities maintenance or scholarships.

Private school staff and boards are very worried about the financial impacts of COVID-19 and the governor’s restrictions on in-person classes.

“It’s been very tough on schools. I get a lot of calls,” Siegel says, adding that some schools are even worried they will have to close permanently. A big reason parents choose to pay private school tuition is for the community, the culture and other human elements, he says. “Online is not what they are going for.”

Shasta Kearns Moore is a freelance reporter and author who lives in the Portland area.

- Your Go-To List for Lunar New Year Family Fun - December 30, 2024

- Ring in the New Year with Family-Friendly Celebrations - December 30, 2024

- January 2025 Digital Issue - December 30, 2024